|

FIGHT FOR COMMUNISM! |

International Communist Workers Party | |

|

| |

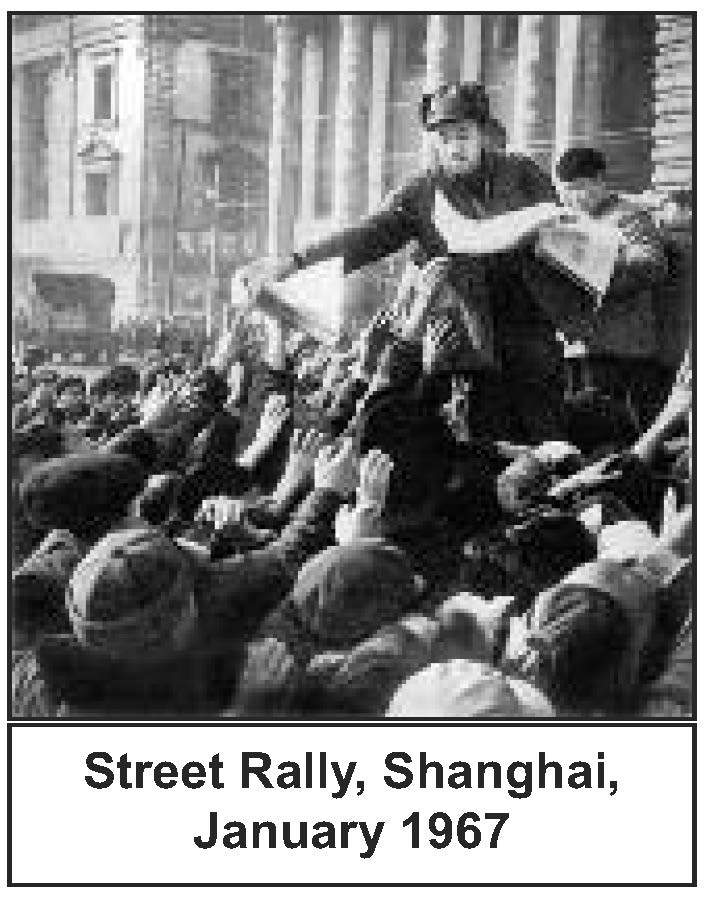

The last article described the “Wuhan Incident” (summer 1967). It pointed toward the importance of mobilizing for communism inside the military today.

The Wuhan Incident sharpened contradictions between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and students and workers who were sick and tired of bloody struggles that only overthrew a few leaders.

In November 1966, two high school students (“Yilin-Dixi”) had written that “the proletarian dictatorship needs to be ameliorated [fixed], the socialist system needs to be reformed, and the form of the Party and the government need to be amended.” They called for creation of “a brand-new state machinery to replace the old one.”

Yilin-Dixi thought they were endorsing Mao’s call for a Paris Commune structure of government. But they were quickly jailed. In February 1967, Mao renounced the Paris Commune model. He condemned their slogan “thoroughly ameliorate the proletarian dictatorship.”

An April article “On New Trends of Thought” argued that power and property were still concentrated in the hands of a few. The main contradiction in Chinese society, it said, was between a “privileged class” of power holders taking the capitalist road and the mass of laboring people. The Cultural Revolution should redistribute property and power.

To many revolutionaries, the Wuhan Incident showed the need to seize military power. During midsummer 1967, mass organizations raided army depots and barracks. They even attacked trains carrying war materiel to revisionists in Vietnam. CCP leaders tried to stop this by promising to arm the “leftist organizations” though not as heavily as their opponents. Fighting escalated across China nearly to civil war.

Mao then demanded an end to all attacks on the army. All arms should be returned. Rebel groups should vie for a share of power on the “revolutionary committees.” Many, disgusted with the infighting, retreated from politics.

By fall 1967, many workers and students became more sharply critical of the CCP. “Ultra-Left” groups began to grow. Their critique of Chinese socialism (“New Trends of Thought” or NT) was more sweeping than any faction within the divided CCP leadership.

NT “ultra-leftists” questioned the roots and goals of the Cultural Revolution. They formed groups such as the “Communist Group” in Beijing, the “October Revolution Group” in Shandong, the “Oriental Society” in Shanghai and the “August 5 Commune” in Guangzhou. The most significant were the Sheng-wu-lian in Changsha (capital of Hunan province) and the Bei-jue-yang (or Juepai) in Wuhan.

Whither China? (January, 1968)

The most influential “Ultra-Left” document was “Whither China?” by 19-year-old Yang Xiguang. He belonged to Shengwulian, which was active from October 1967 to January 1968.

Yang synthesized ideas from many NT groups. He concluded that “over 90 per cent of our high-ranking officials have formed into a unique class—the red capitalist class.”

The CPC’s relationship with the masses, Yang said, “Has changed from that of leaders and followers to rulers and ruled, to exploiters and exploited, from equal, revolutionary camaraderie to oppressors and oppressed. The class interests, prerogatives, and high income of the red capitalist class are built upon repression and exploitation of the masses of the population.”

To create the People’s Commune of China, Yang said, the masses had to forcefully overthrow the “bourgeois dictatorship and the revisionist system of the revolutionary committee.” The existing state must be completely smashed.

He knew that “the revolutionary committee’s road of bourgeois reformism is a dead-end.” It “would take China the way of the revisionist Soviet Union.” If the Cultural Revolution stopped here, “the people will again be returned to the bloody fascist rule of capitalism.”

Yang called for the formation of Maoist groups that could become a new revolutionary party. But, as a dedicated Maoist, he clung to mistaken theories like “two-stage revolution.”

Yang rejected communism as an immediate goal because “the masses have not yet fully understood that their interest lies in the realization of ‘communes’ in China.” He strongly opposed the “leftist doctrine of one revolution.” This was the idea that the revolutionary committee should be overthrown right away and replaced by the commune.

Mao and other CCP leaders had been watching Yang. In November 1967 they launched a campaign against “ultra-leftism” in Hunan. They responded to “Whither China?” with an all-out attack. The CCP called Shengwulian “counter-revolutionary” and “extremely reactionary.” Yang and his comrades got long prison terms.

But the CCP also circulated the essay widely to expose its “errors.” Hundreds of thousands read and debated it in China. It influenced many communists in other countries. Some eventually helped to found our International Communist Workers’ Party.

The next article will describe how the “ultra-left” continued to grow. We will draw important lessons from its great strengths and fatal weaknesses.