|

FIGHT FOR COMMUNISM! |

International Communist Workers Party | |

Socialism in China couldn’t end sexism because it maintained the wage system.

This was the conclusion of a 1987 report on “Women in Rural China.” Two Danish researchers studied documents from 1962-65 (before the Cultural Revolution) and 1970-75 (after). In both periods, the socialist state aimed for increased production. Their goal was to accumulate surplus value extracted from workers’ labor. This shows that socialism was a form of capitalism.

A key Women’s Federation document from 1962 proposed that women should participate in production outside the home (wage-labor) on top of their traditional unpaid responsibilities at home. In rural China “housework” included very heavy labor such as carrying water from the well daily. So the movement of women into social production (wage-labor) did not end or even lessen the burden of sexism.

What was true of socialism is also true of capitalism in all its forms. To end sexism we must mobilize for communism. Communism means ending the wage system that is the material basis of modern-day sexism. Communist mobilization, now and in the future, demands constant struggle against sexist ideas and all the social forms in which they are rooted.

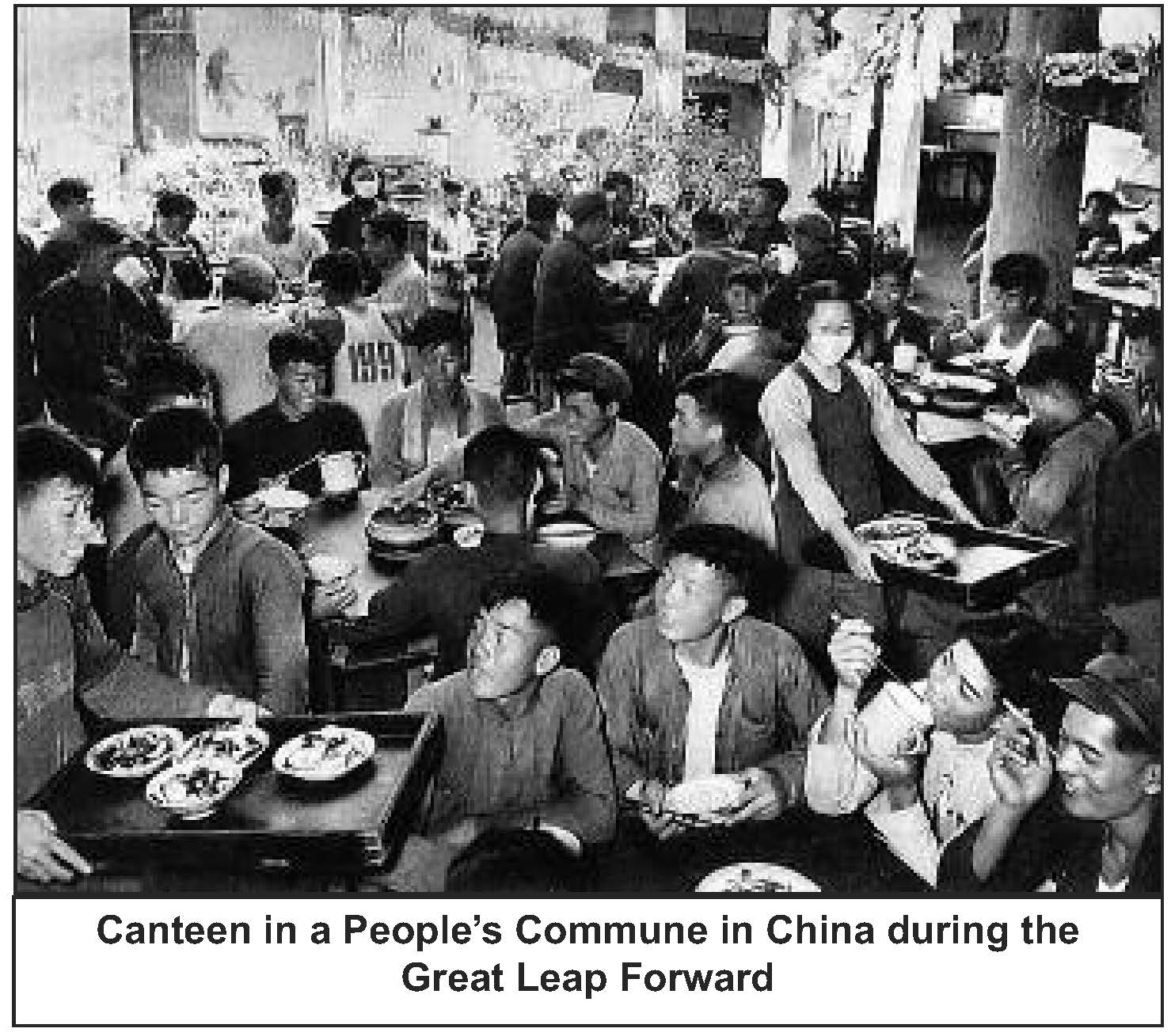

The attitude of the Chinese Party and Women’s Federation was that “all efforts should be judged according to remunerability.” The Women’s Federation did not discuss building collective institutions (like childcare centers or communal kitchens) that might have lightened the burden of housework as women took a larger role in social production. This is striking in view of the fact that such institutions did exist in the People’s Communes during the Great Leap a few years earlier. Then, when “women’s work” was socialized and valued, men would sometimes volunteer to do it.

In both the 1960s and the 1970s China massively mobilized labor for capital construction. This created labor shortages in agriculture. So women were told to do more field work, on top of the work they always did. Official propaganda assumed that the only obstacle was the woman’s attitude and will. The idealized “revolutionary woman” was supposed to prove herself by “doing it all.” Few married women could achieve this ideal.

The only concrete suggestion offered was that older women should do more child care. This increased conflicts between older and younger women. It also left more children to be raised by women who would train them in the old society’s ways.

The slogan “women hold up half the sky” did not mean they would be paid equally, but that their labor was needed to expand the state’s capital accumulation.

On paper, women were to receive “equal pay for equal work.” However, work traditionally done by women (such as picking cotton or harvesting grain) was not considered equal to work traditionally done by men. An hour of “women’s work” was typically allotted fewer work points than an hour of “men’s work.” That meant a smaller share of the total value produced by the collective.

Sometimes the sexism was open. For example, a case is described where women planted more beans. However the men insisted they should get more work points anyway because they were “stronger.”

Even when women and men got work points that were closer to equal, women earned less because they had to take days off or leave fields early to do unpaid housework. Calls for men to “share the housework” were rarely put into practice because their labor outside the home was better-paid. It was assumed that the economic unit was the family household.

When the husband worked in industry, lower wages for women were sometimes justified by

arguing that their husbands were well-paid and the household was doing well. On the other hand, equal wages were sometimes justified with the argument that women would be more motivated to work.

Either way, the official ideology was thoroughly capitalist in content. Abolition of the wage system was not on the agenda. An end to sexism was nowhere in sight.

SOURCE: Vibeke Hemmel and Pia Sindbjerg, Women in Rural China (Curzon Press, 1984)

NEXT ARTICLE: Communism and the struggle to end sexism