|

FIGHT FOR COMMUNISM! |

International Communist Workers Party | |

“Women play an active role in various kinds of work at the Taching Oil Field,” the woman leader Hsin Hua wrote proudly in 1977. “There is practically no housewife at Taching today who is not productively employed, except for the old, weak, ill or disabled.” This wage labor, argued the Chinese Communist Party, was the material basis for the emancipation of women.

Almost all Chinese women were far better off in 1977 than their mothers or grandmothers had been before the revolution. But, as the previous article explained, women still carried heavier burdens than the men in their families because socialism maintained a wage system.

Today we fight directly for communism. The immediate end of the wage system will destroy the true material basis of sexism.

William Hinton recorded a 1971 discussion among communist cadres about the constant quarrels in Little Lin’s poor-peasant family. Veteran Wang thought that the economic question (low wages) was the principal contradiction. Judge Kao replied that the principal contradiction was between old and new ideas of women’s equality.

Kao’s position sounds “left” because he said that “politics is primary.” But Wang was closer to the truth. He asserted that “with higher incomes there will still be economic contradictions … and contradictions in ways of thinking also” though at “a new stage.”

Sexism could not disappear as long as families were dependent on wages (“income”).

In the 1970s, the Chinese Communist Party led a series of campaigns attacking the traditional sexism of Confucianism. Its central theme was rejecting the idea that women’s work was confined to unpaid housework. Women were told to give up their “feelings of inferiority” and engage in wage labor.

The Liu Shao-Chi and Mao factions argued about whether or not women should get “equal pay for equal work.” They agreed, however, that the main goal was increased production.

Neither faction argued for communist social relations, including comradely unity of women and men, the way we do today. Both emphasized changing women’s attitudes, not the material conditions of their lives or even men’s attitudes toward them.

Women were pressured to be “good housewives” while also becoming wage laborers—a double burden. They were supposed to be “frugal” so that wages could stay low for everyone, increasing the state’s capital accumulation.

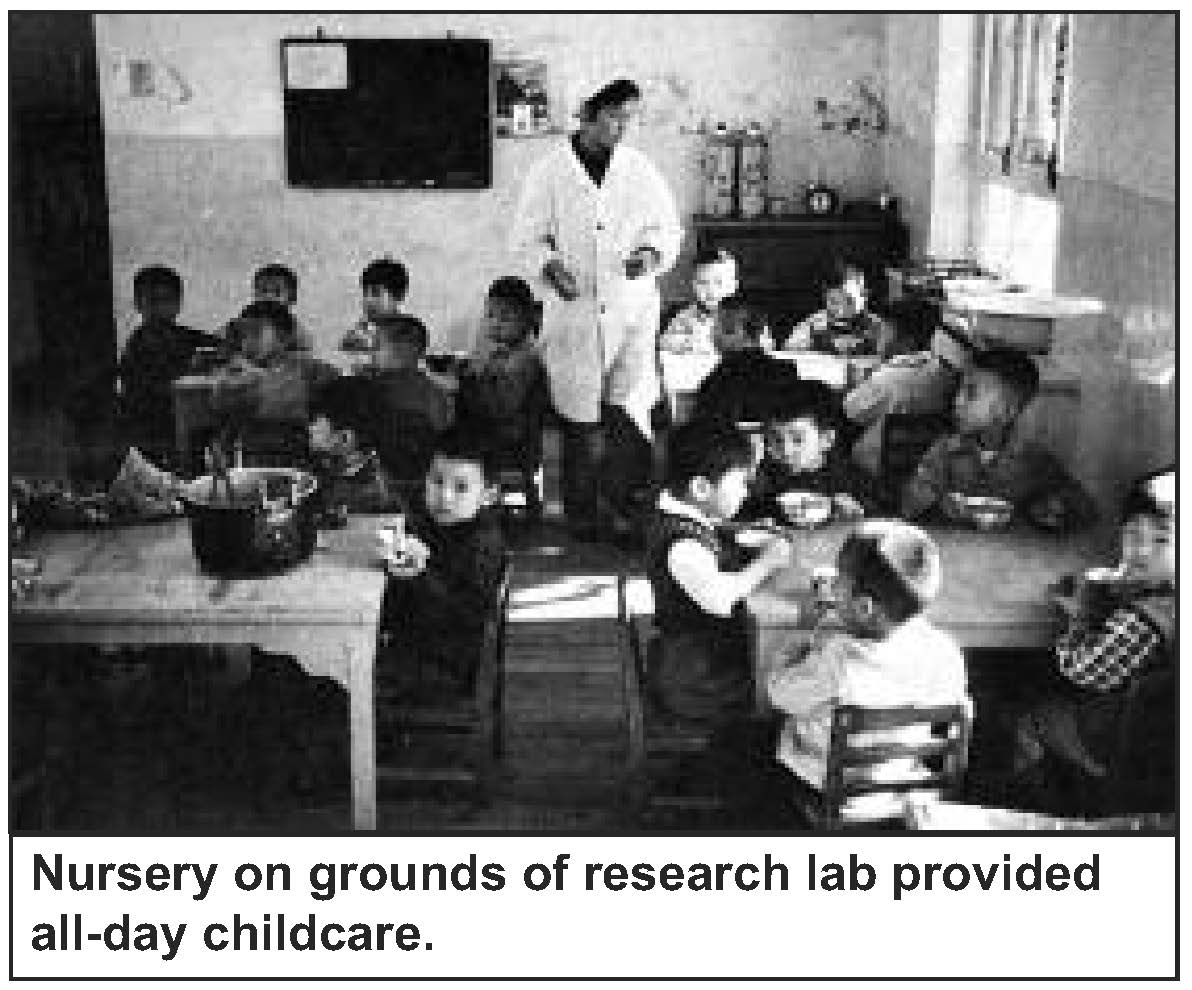

Hinton asked the Long Bow Women’s Association leader why there wasn’t a full-time nursery. “It’s not really necessary,” she answered. Except during the busy season “the women with children stay home, cook and make clothes.”

And, she said, “When others look after your kids you have to give work points. Most people don’t feel it is worth it. If grandparents and old people do it temporarily that’s one thing. But to give work points, that is something else.”

That meant that “as long as the social value of work is not discussed in China, and work remains to be evaluated according to the production of surplus value, that is, as long as the commodity economy remains, women will be tied down in their traditionally belittled roles,” as two Scandinavian researchers concluded in 1984. “In other words, women are not liberated.”

Women’s double-burden was never even described as “transitional” which would have been bad enough. Instead “a virtue is made of necessity and turned into a socialist ideal for all women to emulate and prove they are revolutionary.” The main work of the Women’s Federation, led by the Chinese Communist Party, was the ideological struggle to get women to accept the double-burden of sexism.

Our conclusion is a positive one:

When commodity production is replaced with communism, work will be evaluated in terms of satisfying human needs. Distinctions between work outside and inside the home will be eliminated. Then the sexual division of labor can be ended and sexist ideas defeated. The work of all comrades, women and men, will be respected and valued. Women and men will finally liberate ourselves from the chains of class society.

SOURCES: Vibeke Hemmel and Pia Sindbjerg, Women in Rural China (1984); William Hinton, Shenfan (1983)