|

FIGHT FOR COMMUNISM! |

International Communist Workers Party | |

There was famine in northern China in 1960. Drought shriveled grain in the fields. Rural laborers barely survived on wild herbs and tree leaves, or died.

But in the village of Dazhai, fields were green and crops flourished. The collective mobilization of labor, on communist principles, had improved and irrigated the land. Gates and windows in Dazhai were not locked, as theft was virtually unknown.

Ears of corn began disappearing from fields. One night, harvest guards caught two thieves from neighboring counties. When they brought the prisoners to Brigade offices, the Party secretary Chen Yonggui stepped in.

“Have you eaten?” he asked the prisoners, to the dismay of the guards who were ready to beat them. “Why did you steal our corn?”

“I couldn’t stand the hunger,” one replied.

Chen Yonggui had food brought to them. He dug into his pockets and gave them a few coins and grain ration coupons. A prisoner protested, “I stole, Secretary, you should punish me.”

“This is a new society,” Chen replied. “Our people are hard put, so what kind of argument would I use to justify that I should live and you should die? When you guys get back home, I wish you would try to find a way to deal with natural disasters.”

Many Dazhai people were angry. Chen organized a meeting of key leaders and explained his thinking: “We’d be committing a crime if we didn’t save [people] when we see them dying. And for the price of a meal you get the chance to teach them.”

During the Cultural Revolution, Chen Yonggui and Dazhai were celebrated for their successful mobilization of production. Their bigger contributions, conscious efforts to build communist social relations, were overlooked. These efforts were hobbled by the socialist policies of the Chinese Communist Party. And by 1980, Chen Yonggui and Dazhai were attacked as the Party moved openly to consolidate capitalism.

The story of the thieves is a great example of what we can learn from Chen Yonggui’s early efforts to mobilize masses for communism. It turns upside-down the ideas of “justice” we’ve all been taught in capitalist society. Instead of enforcing laws, he fought to meet everyone’s needs.

It’s in this context that we should view the new City of Los Angeles Restorative Justice project. The City Attorney is setting up “neighborhood courts” in South LA and Van Nuys to use “trained community members” to handle misdemeanors like graffiti. If an individual takes responsibility for an alleged violation, the court would quickly decide how he or she can “make it up to the community,” for example by repainting the wall. The individual would not face criminal charges. That could help the bosses unclog their courts and jails on the cheap.

More important, LA rulers are trying to win workers to the fascist idea of helping to enforce capitalism’s property-protection laws against their neighbors.

The individual will supposedly receive social services like job training. But capitalism cannot provide meaningful work even for those with “jobs.” It can’t provide constructive outlets for the energy and creativity of our youth. It can’t guarantee everyone the basics of nutritious food, adequate shelter, and a healthy environment, even as McMansions spring up and upscale restaurants flourish.

As Chen Yonggui said, isn’t that a crime?

The LA neighborhood courts are supposed to handle “quality of life” issues. But will slumlords or sweatshop owners be hauled into these courts to make amends for racist exploitation?

If you make a mess, you should help clean it up if you can. And the idea of “justice” as “restorative” (making amends) instead of punitive (getting even) certainly seems attractive.

But it’s still the opposite of the communist approach to the corn thieves. They were not made to labor in the fields. Instead, their motives were investigated, their immediate needs were met, and they were encouraged to take leadership in the future.

When we envision communist society, we shouldn’t have the illusion that anti-social behavior will disappear right away. But we shouldn’t plan to carry over capitalist notions of “laws” or “justice” either. Instead, we should engage in a broad discussion now about how to turn episodes of anti-social behavior into opportunities to mobilize the masses for communism.

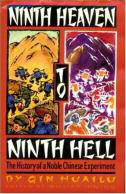

Ninth Heaven to Ninth Hell: The History of a Noble Chinese Experiment (1995), by Qin Juailu, edited by William Hinton. Pp. 148-152