From Red Flag, Vol. 1, #15, September 15, 2010

In the last issue of Red Flag, we discussed the differences between change in the quantity of something, like your age or your weight, and a change in quality, like the change from health to sickness or life to death. In this column, we will look a little deeper into qualitative change, and discuss what happens as qualitative changes follow one another.

A qualitative change can only happen when some aspect of a thing or a process has been replaced by an opposite characteristic, like the solidity of ice being replaced by the fluidity of liquid water when ice melts.

This transition from one quality to an opposite quality is called a dialectical negation.

This use of the word ‘negation‘ does not mean that the transition it describes is something negative or bad. If you have been out of work and find a new job, the transition you make is the negation of your unemployment, which isn‘t a bad thing.

A dialectical negation is never a complete change in all aspects. Some of a thing‘s qualities change into their opposites while others are preserved. A healthy person who gets the flu undergoes a negation from health to sickness, but that person‘s brain, heart, legs, etc., will usually continue to work.

The contradictions inside things drive them to change. Sometimes this change is just change in quantity, but if quantitative change continues far enough, it produces qualitative change, that is, dialectical negation. Another way to put this point is that qualities have quantitative limits. If the rivalry of competing capitalist countries becomes intense enough, they make the transition from peace to war, or from small wars to big ones.

Dialectical negation does not happen all the time, but it does happen eventually. As long as a process lasts, the contradictions in it will drive it to the next negation. History keeps going, one dialectical negation after another. This is part the dialectical law called the Negation of the Negation.

A dialectical negation is never completely reversed. If you have an accident and break your arm, that is a dialectical negation. If your arm heals, that is a second negation. Your arm may seem as good as new, but in fact the structure of your broken bone has permanently changed, even if what is new is too small to notice. In other dialectical negations, the difference is a big one. If a seed grows into a plant (a negation) and the plant produces a new seed with altered genes (a second negation), the new seed may produce a plant with quite different characteristics (a mutation). This is an essential part of evolution by natural selection. Marx described the history of capitalism as capitalists grabbing the land and labor of workers and small farmers (a negation), and communist revolution as grabbing the means of production from the capitalists (a second negation). This second negation does not take us back to pre-capitalist days, but is a huge step forward.

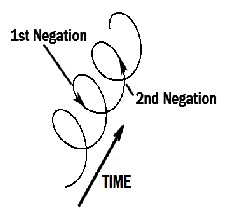

One way to describe how negations follow negations is by comparing a process to a spiral. Each negation is a half twist around the spiral. If you start at the top, two half twists bring you back to the top, but farther along the spiral. So history is not circular. Situations that are similar to the past can happen, but always somewhat different from what happened before. This is the second part of the law of the Negation of the Negation.

Spiral Development According to the Negation of the Negation

Sometimes people describe the result of the second negation as a partial repetition of the original situation on a “higher level.” The result is higher, but only in the sense that the process is farther along in its development.

“Higher” does not mean better. The process of the death of an empire, for example, goes through many dialectical negations that make it worse and worse. As we build up the communist movement, however, we need to use the Law of the Negation of the Negation to understand the course of the struggle for communism. This will be the topic of our next column.