Epifanio Camacho here ♦ Epifanio Camacho Has Left Us here ♦

Epifanio Camacho (1924-2022): Indispensable Communist Fighter, Rooted in the Indispensable Masses

Epifanio Camacho (1924-2022): Indispensable Communist Fighter, Rooted in the Indispensable Masses

“There are those who struggle all their lives. They are the indispensable ones.”—Bertolt Brecht

How do we honor comrade Epifanio Camacho, a working-class hero, without promoting a dangerous cult of the individual? The masses make history, not “great men and women” as capitalist historians tell us. These “heroes” would be nothing without the masses.

Camacho had already made history when he first met our comrades in October 1972. He had helped convince César Chávez to organize a farmworkers’ union instead of a “community service” organization.

But Camacho and Chávez would have been nothing without the fifty workers from the rose farms who came to the first meetings. These workers helped organize a strike that shut down McFarland’s largest rose farm.

Camacho and Chávez would have been nothing without thousands of farmworkers who, inspired by 2,000 striking Filipino grape workers, organized thousands more Latinx workers to strike for a union. That strike lasted five years and won recognition for the United Farm Workers.

Camacho was not yet a communist in 1972. He was a militant class fighter who had defied the pacifist, religious, anti-immigrant, and class-collaborationist leadership of Chávez and Huerta.

Once Camacho became a communist, capitalist historians ignored him. They praised instead faithful anti-communist servants of the bosses like Chávez and Dolores Huerta. They despised the farmworker masses, portraying them as passive, blind followers.

Camacho was never arrogant, despite his long fighting history and his enormous influence and popularity. He was humble and respectful to everyone except the bosses, their supervisors, and strikebreakers.

“We met Camacho in Lincoln Park (Los Angeles),” recounts a comrade. “He was speaking to twenty other strikers about the origin of racism. When he finished, we respectfully explained that capitalism created and propagates racism to divide workers and super-exploit sectors of our working class.

“Camacho responded, ‘That’s what I wanted to say. Thank you.’ He gave us his contact information. We struck up a friendship that lasted almost fifty years.”

This relationship, and an international collective effort, helped develop Camacho into a communist leader of Progressive Labor and later of the International Communist Workers’ Party (ICWP).

From Reformist Struggle to Communist Struggle

The UFW won recognition and its first contracts in 1970. It grew to almost 100,000 members. In 1973, ranchers refused to sign new contracts. The fight had to start over. This showed Camacho the correctness of the communist idea that capitalism cannot be reformed, it must be destroyed.

Camacho began to introduce communism to other strikers, and Chávez expelled him from the UFW. In a public letter distributed regionally, Camacho explained that as a communist he fought to liberate the working class from the bosses’ exploitation and oppression through an armed revolution. He accused Chávez of defending the interests of the ranchers and capitalists. Chávez never replied.

Camacho recruited more farmworkers into a Party collective that distributed hundreds of communist papers every issue for decades.

In 1982 we concluded that we had been mistaken to fight for socialism, which was state capitalism. Our fight should be directly for communism. Camacho and the farmworkers collectives were key to developing and spreading this new understanding.

McFarland became a communist center, hosting annual Summer Projects to train young communists. Many saw that masses supported communist ideas. Workers and youth easily understood Camacho’s comments, which wove together his life experiences and political analysis.

“It was so inspiring to listen to Camacho,” remembers a comrade from El Salvador. “He planted a seed in each of us. From his house we visited homes in the neighborhood, and his experience strengthened us to talk to other workers.”

In the 2000s we realized that despite our communist line, we were mobilizing workers mainly around a reformist approach to fighting pesticide poisoning, racist police, exploitation. Reforms, rather than communism, had increasingly absorbed our time and energy. Without a clear goal of a communist world, some comrades had become discouraged. The McFarland work dwindled. But Camacho struggled on.

Camacho joined the group that broke from PL in 2010 and organized the ICWP. He embraced the guiding principle of mobilizing the masses to fight directly for communism and nothing less.

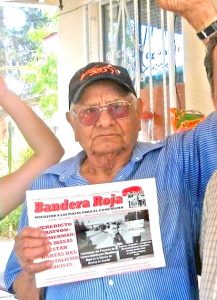

We respond to capitalist attacks on our class with communist class struggles. Instead of formulating reform demands, our political slogans offer a sharp vision of the communist world that we urgently need. Camacho spread our Red Flag newspaper and wrote for it while he was still able.

Camacho was an indispensable communist fighter. And so we must all become.

Comrade Camacho’s story will inspire generations. He raised high the red flag of communist revolution. He helped to develop and implement the most advanced political line of the international working class

Revolutionaries draw encouragement, inspiration, and determination from the masses. Every worker’s small action – taking communist newspapers for themselves and friends, attending a meeting or a demonstration – helps to steel everyone and builds confidence in the masses.

Comrade Camacho was indispensable because of his relationships with the indispensable masses.

Epifanio Camacho has left us, but his legacy continues more than ever

Camacho spent half of his nearly one hundred years organizing for communism. Many workers participate militantly for immediate demands: better working conditions, wage increases, against sexism and racism. However, they stay within that limit and do not join the revolutionary organization to end the system of wage slavery that causes these evils. Camacho, an outstanding leader of workers’ struggles, was convinced of the line of mobilizing the masses towards Communism.

In 1975 I was invited to a Trade Union Conference in San Francisco, California. On the bus I met Camacho, who had joined the Progressive Labor Party, which organized the Conference. I had traveled from Tijuana together with two workers from the Ciudad Industrial del Valle de Cuernavaca, Mexico.

I was surprised by his enthusiasm for the workers’ struggles and by his criticism of Cesar Chávez, leader of the United Farm Workers (UFW), where Camacho had played a leading role in a strike of workers who grafted rose bushes.

At that time, the struggle of farm workers in Texas was taking place, led by Antonio Orendain; Camacho also spoke about this at the Conference. But what impressed me most was his resolve to join a communist party.

I participated in a Summer Project, one of those organized annually in Delano, California. We distributed communist literature house to house and entered a field to talk to the workers. The enthusiasm of the volunteers was great and the farm workers, Camacho’s neighbors, collaborated by lodging us and contributing for the stay.

Camacho traveled several times to Oaxaca, Mexico, to help grow the communist organization. Some comrades there had joined the Party in the San Joaquin Valley under Epifanio’s leadership. He met my many brothers as they were staying with us when he was in Mexico City.

In the last ten years we both joined the communist effort led by the International Communist Workers’ Party.

We will always remember Epifanio Camacho as a great communist.

—Comrade in Mexico