This past January marked the 50th anniversary of what is known in Britain as “Bloody Sunday.” On January 30, 1972, fifteen thousand people marched unarmed for civil rights in Derry, Northern Ireland. It ended in a massacre by British troops.

Workers in Derry had taken over part of the city, with self-defence, a radio, and mutual aid. This self-rule is a small example of how workers can run society without the capitalist bosses. These moments terrify the ruling class and can inspire us to mobilize the working masses for communism. For this we can and must break the bonds of nationalism and sectarianism.

The north of Ireland was, and is still, under British colonial occupation. In 1972 its rigged political system favoured this occupation. The 1972 marchers were predominantly of Catholic background. They were persecuted by the “State of Northern Ireland” which was controlled by the secretive Protestant Orange order.

Protestant “loyalists” supported British rule and Catholic “nationalists” sought to unify Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland. These nationalist aims were pitted against each other to divide the working class.

English occupation of Ireland goes back centuries. So does the use of Protestant settlers from Scotland and England to divide and conquer. A nationalist movement among Irish Catholics led to a civil war from 1919 to 1921. It ended in the division of Ireland between an independent Irish state and Northern Ireland, an enclave of British rule.

Communists throughout Ireland responded to the attacks of the Great Depression of the 1930s by organizing the Revolutionary Workers’ Groups (RWG). In Northern Ireland these organized the Outdoor Relief Workers Committee in July 1932, to oppose a work-for-welfare scheme. When police and “special constabulary” attacked striking unemployed workers in Belfast, Protestant and Catholic workers from throughout the city fought side by side in a full-scale riot that lasted several days.

This unity remained solid. The RWGs mobilized actions on both sides of the border, ending in the 1933-34 Ulster railway strike that involved both Catholic and Protestant workers. But by 1935, the ruling class had regrouped. It was again able to whip up Protestant workers into communalist (sectarian) violence, driving Catholics from their homes and streets.

These events would be repeated 30 years later. A civil rights movement emerged in the north of Ireland. It was inspired by the US Civil Rights movement and the struggle of Vietnamese workers and peasants against US imperialism.

Anti-Catholic violence continued throughout 1969 and Catholic working-class communities began to fight back. British troops were deployed, ostensibly to “protect” the Catholics but in fact to protect the Orange state against the rising militancy of working-class youth.

By 1972 the “Troubles” between Protestants and Catholics had become civil war. There was massive opposition to British occupation. Working-class communities began to resist British imperialists and their Orange state in a variety of ways, particularly on the council estates (working class housing) of Creggan, Bogside and Turf Lodge.

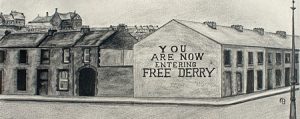

From ‘69 -’72, part of Derry became an autonomous area, resisting patrols by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the police force and British troops. For one week in ‘69 and later in ‘71 it was a no-go area for the RUC and military. The working class organised their own forms of defence, including “Radio Free Derry,” mutual aid, barricades, bomb factories, first aid posts and citizen volunteers who dealt with crime and punished offenders.

That an urban working class could develop such self-rule was a remarkable achievement. It’s a key reason we should commemorate Bloody Sunday. And it was a dangerous precedent the armed forces of British imperialism could not accept.

A peaceful demonstration that Sunday was to leave Creggan and march to downtown Derry. The military had unannounced plans to create a confrontation as the marchers left the estate and use the confusion to retake the area. Secretly they replaced their regular troops with a crack paratrooper unit. Their plan worked. Within ten minutes, thirteen lay dead and fifteen were seriously wounded. Armoured vehicles raced into Creggan.

The British ruling class and the so-called independent media have lied through their teeth about this for generations. We remember Bloody Sunday to honour our working-class heroes and to salute the tremendous achievements of the working-class families in those estates. Their ability to create such sophisticated no-go zones, under such repression, demolished the corrosive notion that ordinary workers can’t run society. We can, and communism can work!