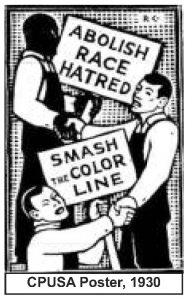

The vision of Communism opened up new avenues of struggle against racism in the United States. For the first time, the potential to end racism became real.

Many cadre strained to break free of limits imposed by compromises with capitalism. Black, Mexican-American and immigrant communists often took the lead. We must build on their efforts to finally free our class of this racist scourge

Socialism Comes to the United States

The French Revolution gave birth to movements that for the first time called themselves “socialist” and “communist.” They were “Utopian,” based on a predesigned ideal communal society.

In the early 1800s Utopian ideas spread to the USA. These early socialists had a bad record on racism. Their organizations typically excluded even freed slaves. The Utopians were indifferent to the abolitionist movement. They argued that the abolition of private property and wage slavery would automatically free black people, without any special effort.

This all changed after the 1848 revolutions in Europe and the publication of the Communist Manifesto. Communism was put on a scientific basis. Instead of predesigned ideal communities, the struggle for communism came out of working class struggle. The key role of the proletariat was made clear. Marx summed it up during the US Civil War saying: “Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.”

Tens of thousands of radicalized refugees fled Germany for the USA. One of the leaders was Joseph Weydemeyer, close friend and collaborator of Marx.

Weydemeyer founded the American Workers’ League. It was open to workers “without respect to occupation, language, color or sex.” The League didn’t last, but Weydemeyer worked hard in the abolitionist movement and the Republican Party. The German émigrés mistakenly buried themselves in the antislavery movement, almost suspending agitation for communism. Then they made the opposite mistake; they assumed the abolition of slavery resolved the whole race issue.

The New Socialist Party Takes a Stand Against Racism

In 1901, most socialists joined the Socialist Party of America. There were only three black delegates at the founding convention. However, the convention approved a resolution for “equal rights for all workers without distinction of race, color or sex.” It urged that black workers join unions and the Socialist Party.

Some white delegates objected to paying special attention to black workers. But William Costley, one of the black delegates, argued successfully that black workers “occupy a peculiar position among the laboring class.” He argued they were subject to extra exploitation and to hatred from both the bosses and some white workers.

The racist dissidents did manage to eliminate a clause denouncing lynching, on the grounds that it would make it impossible to organize in the South!

The Socialist Party had tens of thousands of members, dozens of daily newspapers, and played a leading role in unions. But it did not a have one central line. Their newspapers could print what they wanted. For a while the 1901 resolution was ignored.

Nonetheless, the left gradually gained strength and fought the white supremacists. Hubert Harrison, a leading black socialist intellectual put his finger on the heart of the matter. “In short,” he said, “the exploitation of the Negro workers is keener than that of any group of white workers.”

Communism Comes to the US

After the 1917 Russian revolution, the Communist International (Comintern) recruited the most militant class fighters. In the US, most were European immigrants. Many prominent black US communists were from the West Indies. They regarded black workers’ struggles as part of the crusade against capitalism and imperialism. It looked like the communist movement had finally gotten on top of the racism question.

However, almost nothing was said about racism at the founding convention of the US Communist Party (CPUSA). The Comintern noticed.

The Russian communists’ experience taught them that the fight against racism was crucial. Unfortunately, they framed it as a “proletarian national question.” The Comintern directed the CPUSA to prioritize the “Negro question.” It agreed.

Shortly thereafter, the “trial” of Finnish party member August Yokinen put the anti-racist struggle front and center. He had objected to black workers attending a social at the Finnish Language Association hall.

A “workers’ court” convened on March 1, 1931. Fifteen hundred attended. Black communist leader Richard Moore led the defense.

Moore blamed “this vile, corrupt, oppressive system.” He agreed Yokinen “must be condemned,” but offered mitigating evidence. His client didn’t benefit from the party documents denouncing racism because he couldn’t read English.

Yokinen confessed to being “under the influence of white chauvinism ideology.” He pledged to fight racism in the future. The court expelled him from the party, but recommended he participate in anti-racist struggles and reapply. He accepted the verdict.

Trials like these became “sensational news for all America” and inspired “a big wave of sympathy and approval” from workers of all races. For the first time, large numbers of black workers joined the CPUSA.

Yokinen himself led a march through Harlem, NYC, to support the Scottsboro Boys. The US government quickly deported him. The Scottsboro Boys were six black teenagers framed for rape in Scottsboro, Alabama. The CPUSA hired a lawyer through their International Labor Defense (ILD) organization, but more importantly built a nationwide movement that saved their lives.

Many new black communist leaders came from the steel mills, mines and farms of Alabama.

Convict labor in this region enslaved hundreds of thousands. They were literally worked to death. U.S. Steel beat, whipped, starved and murdered thousands. Hundreds of unmarked graves in forests surrounding the steel and coke factories testify to the brutality. “Jim Crow” laws insured this cheap enslaved labor pool, dragging down “free” labor as well.

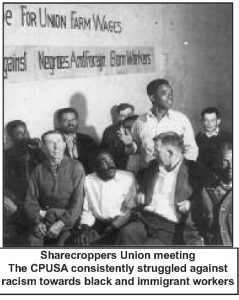

The Communist Party had three members in Birmingham in 1929. Ninety joined by August 1930. Over five hundred joined Party mass organizations: almost 90% were black. District organizers noted “Negros… are the decisive strata among the toiling masses in the South.”

Black communist leadership was also forged in the armed combat of Alabama sharecroppers. In Reeltown AL, the CPUSA-led Sharecroppers Union fought a 24-hour armed battle against the Sheriff’s department and Klansmen over the repossession of livestock. As a result, the Communist Party National Negro Commission demanded “the abolition of all debts owed by poor farmers and tenants, as well as interest charged on necessary items such as food, clothes and seed.”

Mobilizing for communism could never have been more appropriate. Communism will not only abolish “debt peonage,” but also all debt, banks and money. The means of production will be collectively owned. This will destroy the material underpinnings of racism.

Unfortunately, the CPUSA never explicitly advocated communist mobilization. Any possibility of such a plan was finally cut off by two big international compromises with capitalism.

Mexican American Communists in the Southwest

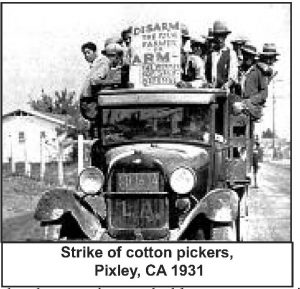

The CPUSA also recruited many Mexican and Mexican-American workers. In 1928, the Comintern decided communists should organize “revolutionary” unions instead of working within all-white unions. In the Southwest, this meant organizing Mexican and Mexican-American workers.

Racism forced these workers into the lowest-paid and most insecure jobs. Here too, organizers had to fight racist vigilantes as well as bosses.

The CPUSA-led coal miners’ strike in Gallup, New Mexico is of particular interest. The party recruited 150 Mexican miners before the strike, organizing cells in every mine. They emphasized “the revolutionization of the striking workers,” not just gaining “material results.”

In 1933, the miners struck. They faced martial law. The state militia escorted scabs into the mines. Workers were evicted from company housing, arrested and threatened with deportation. The strikers, often led by women armed with clubs, attacked scabs and the National Guard.

When the strike ended, the bosses black-listed Mexican organizers and deported many communists. The ILD, the same organization that defended the Scottsboro Boys, fought against the deportations and repatriations. They called them imperialistic and racist.

Once again, communist mobilization would have been the only real remedy. Communism will answer imperialism and racism by eliminating nations and borders altogether. Production will be organized collectively to fulfill the needs of the world’s workers. Profits and empire building will not enter the picture. But compromises with capitalism once again shut the door on mobilizing for communism.

Nationalism and the Black Belt

In 1928 the Comintern said southern U.S. blacks were a separate national group. Therefore the fight against racism should demand self-determination through national liberation of the southern “Black Belt.”

The CPUSA agreed but the whole business never made much sense. The “Black Belt” line never helped recruit or inspire organizing.

In practice, many rank-and-file communists rejected the false choice between the anti-racist reform of capitalism and revolutionary nationalism. In particular, black, Mexican-American and immigrant communist leaders took aim at racist super-exploitation.

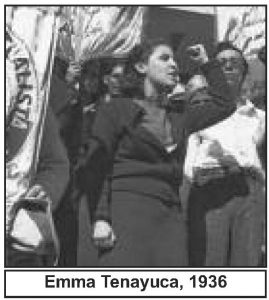

Emma Tenayuca, communist leader of the 1938 San Antonio walkout of pecan shellers, put it clearly during the heat of the strike. She argued that Mexican-Americans were a separate ethnic group, subject to racist exploitation. Most importantly, they could only achieve liberation in the struggle of a united working class. Given the option, why couldn’t communist leaders like her be won to mobilizing for communism directly?

The “Black Belt” line was so unpopular that it was reduced to a “Sunday Ritual.” It was quoted in literature, but rarely discussed at a grass-roots level. Party leader Earl Browder conceded, “The [Black Belt] slogan [need not] be immediately transformed from a propaganda slogan into a slogan of action.”

United Front Against Fascism

This nationalist error was compounded by another Comintern initiative, the United Front against Fascism (1935). This meant supporting the racist Roosevelt administration and its New Deal even though it often excluded blacks and Mexicans.

The New Deal built Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps to relieve poverty and train young workers in forest conservation. They were racist and segregated. In February 1934, Young Communist League (YCL) activists organized a strike of two hundred black workers in a camp near Tuscaloosa, AL. State troops intervened. The strikers retaliated with bricks. New Deal executives fired 160 workers, arresting YCL strike leader Boykin Queenie. The CPUSA built a campaign demanding his release. Unfortunately, this kind of anti-racist activity against the CCC ceased under the United Front.

In 1931, black communist leader Harry Haywood criticized the party’s newspaper for printing a statement by William Pickens, the NAACP’s field organizer. Pickens advocated a coalition led by mass organizations of the CPUSA and the NAACP. The Communist Party reversed course under the United Front. It ceded leadership to the NAACP’s legal team.

Hosea Hudson, a black communist veteran of armed struggle in Alabama, put it simply when referring to on-the-job work. The United Front shrunk the party because “everyone got soaked up in the [CIO] union.”

During World War II, the CPUSA’s fight against racism, and class struggle in general, took second place to fighting Hitler. Many fightbacks were squelched. Those allowed had to “aid the war effort.” For example, the CPUSA-organized Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee fought racist attacks against Mexican youth, including the Zoot Suit Riots. The rationale was that these attacks made the U.S. look bad, hurting the war effort.

This reached a critical stage in 1944 when Earl Browder dissolved the Party! It was revived soon after but buried any mention of communism in its political work. CPUSA cadre effectively built anti-communist, reform organizations like the NAACP, while extolling the Democratic Party as the lesser of two evils.

Despite these derailments, leading black figures like Paul Robeson and W.E.B Du Bois continued to fight, undeterred by government sponsored anti-communism in the 1950s and 60s. Their confidence that communism would eventually end racism demands we mobilize the masses for communism and nothing less.

Communism and Anti-Racism Revived

In 1965, some communists who were sick of the CPUSA’s resistance to mobilizing for socialism and to fighting racism formed Progressive Labor Party (PLP).

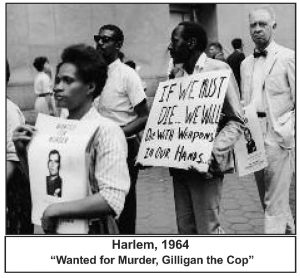

PLP had early success organizing during the Harlem anti-racist rebellion. In 1968 they declared that all nationalism was reactionary. Until then, the whole communist movement believed that the nationalism of the oppressed was “objectively progressive.”

After campus PLP groups attacked the pseudo-science of academic racists, PLP formed the International Committee Against Racism (InCAR) in 1973. InCAR became well-known for fighting anti-busing racists, Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan. But in practice, PLP abandoned the fight for communism for a program of militant anti-racist reform struggle. For example, the campus campaigns said little about communist education.

In 1982 PLP declared that communists should fight directly for communism. Workers should abolish wage-slavery and money immediately after seizing power. Socialism had never led to communism and never would.

Unfortunately, this was a high-water mark and was never really put into practice. Eliminating wage slavery may have been the goal, but the implications were rarely discussed. The party’s newspaper had little concrete to say about communism. Instead, it used its space to expose capitalism and to push militant reform struggles.

Birth of ICWP

In 2010, a good number of members fed up with PLP’s resistance to mobilizing for communism founded the International Communist Workers’ Party (ICWP). We make the fight for communism our daily struggle.

For example, the lead article in this pamphlet explains how communism will end racism, and what form the struggle against racism will take after the revolution. We have no illusion that short of a revolution we can make any permanent progress against racism.

This article on the history of racism has much to say about the history of communism. The reason is that only communism can abolish racism.

What makes us think we can do any better than our predecessors? Because we stand on the shoulders of communist-inspired masses. It’s almost exactly 100 years since the Russian revolution, more than 150 years since the publication of the Communist Manifesto, and almost 500 years since the publication of Utopia. We have 500 years of experience to draw on, 150+ years of Marxism and a whole century of masses struggling for communism and against racism.

This experience is hard-won and priceless. We will still make mistakes, but there are many mistakes we won’t make. That includes underestimating the central role of the fight against racism. Communism will knock down the pillar upon which racism stands: wage slavery.

This time we will succeed.