Sexism and Class Society: Don’t Blame Neolithic Farmers. Let’s Choose to Live Our Collective Lives as Communists

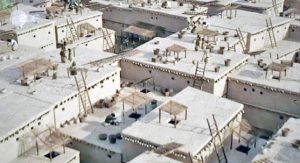

LOS ANGELES (USA), March 11— “To see an agricultural society that existed over a very long time with no evidence of inequality was deeply meaningful to me as a communist,” a comrade said. She was reflecting on having seen the remains of the neolithic community Çatalhöyük (in today’s Turkey) that flourished from 7400 to 5900 BCE.

Our book group was discussing the chapter of The Dawn of Everything that describes Çatalhöyük.

“One kind of building – people lived in them,” the comrade continued. “No government or church or temple buildings of any kind. Just places where people lived the richness of their lives…close together with ladders up to the ceiling and interconnected rooftop communities. No castles or palaces.

“I had thought that because agriculture created the possibility of surpluses, it inevitably led to class society, a state to enforce it, and a church to justify it, like medieval Europe. But the authors got this right. Agriculture did not make class society inevitable.”

Ernie had summarized the chapter’s main point: “The move toward agriculture was slow, playful, led by women, and tended toward equality and peace not patriarchy and violence.” The evidence the authors presented includes:

Studies of human teeth and skeletons at Çatalhöyük reveal a basic parity of diet and health for men and women. So does the ritual treatment of male and female bodies in death.

There is no evidence of central authority in Çatalhöyük and not many “explicit signs of rank.”

People may have farmed in warm months and hunted in winter months. They practiced flood retreat farming, which requires “little central management” and has “a built-in resistance to the enclosure and measurement of land.” This lent itself “toward collective holding of land, or at least flexible systems of field reallocation.”

Evidence from this and other sites indicates that “the ‘Agricultural Revolution’ took 3,000 years, much longer than it should have if it had been an inevitable trap. For much of that time people seem to move in and out of it as they deemed practical.”

And the Neolithic world was not “simple.” The authors argue that “Most of humanity’s greatest scientific discoveries – the invention of farming, pottery, weaving, metallurgy, systems of maritime navigation, monumental architecture, the classification and indeed domestication of plants and animals, and so on – were made under precisely those other (Neolithic) sorts of conditions.” Much of it, they assume, must have been done by women.

“Is that really true?” someone asked.

“Yes,” replied Marcia, who has read a lot about the history of science. She recommended Science in History (1954) by the Marxist J.D. Bernal. It’s limited by the traditional “stages” framing of human history and by not having had access to the last half-century’s archaeology and anthropology. But it does treat Neolithic accomplishments as real and important science.

Eleanor, an anthropologist, offered that, if anything, the authors of The Dawn of Everything overemphasize gender differences in neolithic social roles. They promote a mythical ideal of women that assumes women and men are essentially different in outlook. They take for granted that gendered work roles have always existed. Much recent research contradicts this “dichotomous” (either/or) thinking. Women were hunters (and cave artists) as well as gatherers, for example.

“My step-brother lived in Bali in the late 1960s,” Nina shared. “There was no hierarchy in his village. Everyone lived in a large dwelling and shared the tasks. They worked in the fields together. There was no pressure to do more or get more. There was no ruler; decisions were made by communal discussion.

“I realize now,” she concluded, “that it was an example of how society could be egalitarian and agricultural at the same time.”

“Does how you obtain subsistence determine how you organize social structure?” asked the first comrade. “This is the key question. That’s why Çatalhöyük is so important. Agriculture did not necessarily lead to a class system or gender inequality.

“This has huge implications. Folks can decide how to live our collective lives. “

“That’s why this book gives me hope,” Ernie concluded.

More on Sexism here More on racism here