From the Chinese Revolution to the Present and Future

Mobilizing masses for communism creates the material basis to end sexism. We can’t say that too often!

In capitalism, working women too often have to put up with sexual harassment, abuse and worse. Like all wage slaves, they need that paycheck to survive. And would anywhere else be better?

In communism, there won’t be wages or money or markets. There won’t be bosses to profit from dividing the working class and super-exploiting black, immigrant, or female labor. Everyone will receive the necessities of life, so we won’t be slaves to a job. If you don’t like something happening where you work, join the communist collective of workers there who are giving leadership!

But will ending the wage system automatically end sexism? No. Even after communist revolution, ending sexism will take a conscious, committed long-term political struggle against the ideas and habits inherited from class society.

That struggle starts now.

The Chinese Revolution: Fighting Sexism by Mobilizing Masses

William Hinton’s book Fanshen is a very helpful first-hand report on the communist-led struggle for land reform in Long Bow, China in 1948. In a chapter called “Abuses of Power” he wrote about a group of Party members who had become militiamen based on their heroism in the revolutionary struggle. But now they bullied men into coming to seemingly endless meetings. They helped themselves to fruit and other things they took, without authorization, from better-off villagers. And they engaged in “rascal behavior” including rape.

Why didn’t the militia leader or the Party collective stop them? They tried – half-heartedly. The key male Party leaders also felt entitled to some privileges, including sexual “favors.” They hit on many women, single and married. Their power was political, not economic. For example, when a former landlord’s daughter rejected him, Yu-hsing arrested her on charges of spreading false rumors.

Hinton relates how these cadre eventually had to stand before mass meetings where they criticized themselves and heard the criticisms of the masses. These criticisms were not always valid, but some felt pressured to accept them anyway. Others – including the clique of abusers—resisted. Hearing these stories, we can understand better the importance of both mobilizing the masses and practicing criticism and self-criticism today. We can’t build communism without them.

Hinton reported on his return to Long Bow in 1971 in another book, Shenfan. This is even more interesting. One thing we learn, for example, is that the “criticism and struggle” process didn’t always work.

For example, during land reform, the militiaman Man-hsi had raped many women. Most were either from landlord or rich-peasant families who had been dispossessed. Others were daughters of hated collaborators. He was criticized sharply for this and promised to change his ways. But four years later he raped the daughter of a neighbor. Only then was he expelled from the party, although he remained a leader in production.

Hinton found that the communist-led movement for land reform and socialism, including the Cultural Revolution, had struck a blow against sexism. For example, young men told him that “in the old days there was no way of making a living. People like us could not afford a wife. Therefore they did questionable things. Now we would be ashamed to do anything disgraceful.” Women said, “Now that divorce is possible there is no need to die.”

We don’t agree with Hinton’s 1971 analysis of the Cultural Revolution (which he later revised). But there is much to learn from his stories about Chinese communists’ pioneering efforts to address crime and anti-social behavior with the “mass line.” And he did recognize that the socialist line “to each according to work” was intensifying economic inequality, not ending it.

Sharp, Principled, Open Political Struggle: Now and Always

Sexism was clearly an ongoing problem in the Chinese Communist Party in spite of its line that “women hold up half the sky.” Is there sexism in the International Communist Workers’ Party today in spite of our best efforts to understand and fight it? Yes. Can we defeat it? Yes.

That conscious, committed long-term political struggle against the ideas and habits inherited from class society starts now. We can’t walk away from it. We won’t be able to walk away from communist society when we inevitably encounter reactionary or even corrupt behavior. We and our friends have to see, in the practice of our party now, that open and honest criticism and self-criticism will make it possible to defeat sexism in the process of mobilizing masses for communism.

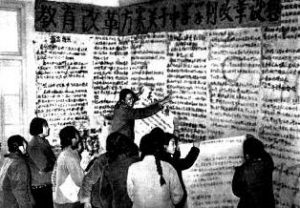

Women engaging in ideological struggle during the Cultural Revolution in China

Women engaging in ideological struggle during the Cultural Revolution in China