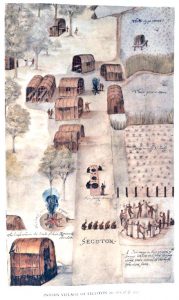

Indigenous village of Secotan on Roanoke Island (now part of North Carolina, USA) as painted by English artist John White in 1586. Notice the images of collective life and equal-sized dwellings among the corn fields. This is one of many examples of an egalitarian agricultural society.

LOS ANGELES (USA), March 3— “Private property took away our freedom,” Nina declared. We were continuing to discuss The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow. We want to learn what we can, from prehistory and cross-cultural comparisons, about the possibility of an egalitarian future.

This discussion led us to think more deeply about what we mean by “egalitarian.” And how to describe more accurately the kind of society we hope and work for.

We agreed with Nina. But this book attacks that idea, even as it also attacks the dominant ideology that capitalism is the only way for people to live today. The authors reject the goal of “egalitarianism” (meaning communism). It is “slippery,” they say, meaning different things in different societies.

They describe an egalitarian society as one where (1) “most people feel they ought to be the same” in some important ways, and (2) that ideal is “largely achieved in practice.”

When we talk about communism as “egalitarian” we don’t mean the capitalist ideal of “equality before the law.” Or liberal (and socialist) ideals like “equal pay for equal work” and “one person, one vote.” Liberals don’t criticize capitalist ideals, just that it doesn’t achieve them in practice. In contrast, communism will have no wages, “equal” or not. And it will mobilize masses for real participation in making decisions, not in an occasional election.

The authors don’t critique capitalist ideas about equality. Instead they “imagine” a society where everyone believed they were “equal before the gods” but half of them had no property or legal rights. This takes them back to their critique of the “stages” theory of human history.

Lots of evidence shows that it’s not true that humans moved from foraging “up” to agriculture and on “up” to modern capitalism. But the authors go beyond their facts to argue that how people produce what they need has little or no connection to how they organize their society. They acknowledge Marx briefly but throw out historical materialism along with capitalist ideas of “progress.”

We aren’t convinced. Eleanor, our anthropologist, commented that the authors often knock down “straw people” instead of confronting real arguments. They “tease” us with fascinating tidbits of information but use them in doubtful ways.

For example, men in some New Guinea villages “hide” secret musical instruments from the women. Marxist anthropologists who lived among these folks analyzed this in terms of the ideology and practice of sexism.

But the authors see these secret instruments as a model of private property. Since that society doesn’t have a “state” they argue that private property is linked instead to “the sacred.” They imply that there is nothing fundamentally wrong with private property.

“You can’t swallow it all at face value,” remarked Nina.

Ernie connected the book’s focus on “freedom” (in contrast to “equality”) with Graeber’s anarchism. “Freedom,” he noted, has as just as many interpretations as “equality.” It’s just as slippery.

The anarchist view elevates individualism. “Individuals were routinely on the move for [many] reasons,” the authors write, “including taking the first available exit route if one’s personal freedoms were threatened.” Linda pointed out that people leaving the society they grew up in would have been unlikely to survive unless they left in groups. Humans are social animals.

So what would be “equal” (the same for everyone) in a communist egalitarian society?

Our group agreed that everyone will have equal access to the resources they need: housing, health care, food, water, and much more. Everyone will have equal access to political agency: the ability to help shape our collective lives. People have different needs, skills, and commitments to the collective, but we will value each other equally.

Or maybe, Marcia suggested, communism’s core values are neither “freedom” nor “equality.” Perhaps they include solidarity— standing with and for each other. Cooperation (collectivity). Hospitality—caring for everyone’s needs, wherever they go. The ability of the masses to shape society. To make decisions for oneself in the context of the collective.

“Think for yourself, but act for others.” How we organize society depends on how we resolve contradictions between collectivity and autonomy. We look forward to reading other comrades’ thoughts.

Read our article series on the history of humanity: “Communism: Our Heritage and Future” here