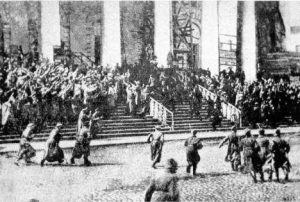

A production of “The Mystery of Liberated Labor.”

“Here a person can understand socialism in his heart better than he can at home in his head after reading a whole library.” This is how a visiting Swedish worker described the effect of watching “The Mystery of Liberated Labor.”

“Liberated Labor” was a mass spectacle produced in Petrograd (later, Leningrad) in the first years of the Russian Bolshevik revolution. The Revolution was a real festival of the oppressed. It unleashed the joy of the masses and led to new forms of theater that involved the masses as participants and not just spectators.

The first big occasion was the November, 1918 anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution. The Moscow celebration featured a huge parade and speeches by Lenin, but also dozens of theatrical performances in twenty-one theaters. Every musician available was employed making music in clubs, union halls, and free theaters. At night, effigies of capitalist leaders and class enemies were burned for forty minutes. This was followed with fireworks and the raising of the new emblem, the hammer and sickle.

In terms of theater, Petrograd tried to outdo Moscow. The Petrograd specialty was street theater (later sometimes called “guerilla” theater). Flying troupes spread throughout the city on platforms pulled by trucks and streetcars. The performances included skits, clowns, and songs, and lasted 15 minutes or so.

In March 1920 a Red Army group put on “The Fall of the Autocracy,” the first mass spectacle. As Richard Stites wrote in Revolutionary Dreams, “actor soldiers representing the autocracy and the Revolution spoke lines from the press, held stylized meetings, sang, and simulated combat.” “The Fall of the Autocracy” was so successful it was repeated 250 times in barracks, camps and squares around Petrograd.

Experienced and classically-trained artists got enthusiastically involved and the productions got more ambitious. On May Day 1920 they performed “The Mystery of Liberated Labor.”

This spectacle dramatized the history of working people trying to break through the golden gate of the “kingdom of brotherhood and equality.” Spartacus, Stenka Razin (a Cossack rebel against Tsarism) and the sans-culottes of the French revolution attack the rulers, but are crushed. Finally, a red star rises in the east. The Bolsheviks break through the gates and scatter the exploiters. In the finale, ships on the river light up the scene, cannons in the nearby fortress go off, four bands play the Internationale, and the audience merges with the performers to join in singing. There were four thousand performers and thirty-five thousand spectators.

Three other spectacles were produced in Petrograd alone that year. The new art form did not last, however. After the civil war was over the army withdrew its support and the spectacles ended. Soviet art reverted to the capitalist model in which a handful of elite stars (whether ballet or film) perform for a massive but passive audience.

We can learn a lot from the experiments with communist theater during the civil war. One lesson is that everyone can play a role in producing great art. We can be sure that many of the four thousand performers of “Liberated Labor” were relatively unskilled. And that at the same time they learned a lot from producing it.

In communism we will mobilize the masses for communist art. In fact, we can start now! We can sing songs, rap, make posters and paintings, put on plays, dance. What a great way to involve people in fighting for communism!

Organizing Creative Arts to Create Communists

The Bolshevik mass spectacles involved hundreds of relatively unskilled and inexperienced performers – ‘amateurs’ – but were anything but amateurish. The amateurs made up for their lack of experience with their commitment and discipline. Putting on a performance with thousands of performers is practically a military operation.

The organizers included a small group of experienced artists who were professionals in the old society. One of the main leaders was Platon Kerzhentsev, a veteran Bolshevik and co-founder of the left-wing Proletkult (Proletarian Culture) organization. Kerzhentsev had spent several years in exile in the West and used the time to study new trends in theater.

He was impressed by the Hampstead (UK) “St George and the Dragon” traditional spectacle put on every year. It was a joint work by the whole community and involved hundreds of villagers. They did everything from performing, to playing music, to painting props.

Kerzhentsev returned to Russia after the revolution and helped the Red Army theater workshops produce the mass spectacles. They took the Hampstead approach and scaled it up by a factor of ten.

Kerzhentsev worked out a theory of mass artistic production, and described it in his book “Creative Theater.”

Kerzhentsev insisted that the people’s theatre was not a theatre for the people but a ‘theatre of the people,’ i.e. based on the creative work of the working class. He said that “the task of the proletarian theatre is not to produce good professional actors who will successfully perform the plays of a socialist repertory, but to give an outlet to the creative artistic instinct of the broad masses”.

Unfortunately, once socialism (as opposed to communism) tightened its grip, Soviet theater became what Kerzhentsev had warned against.